Spotlight

William Morton Comes Home

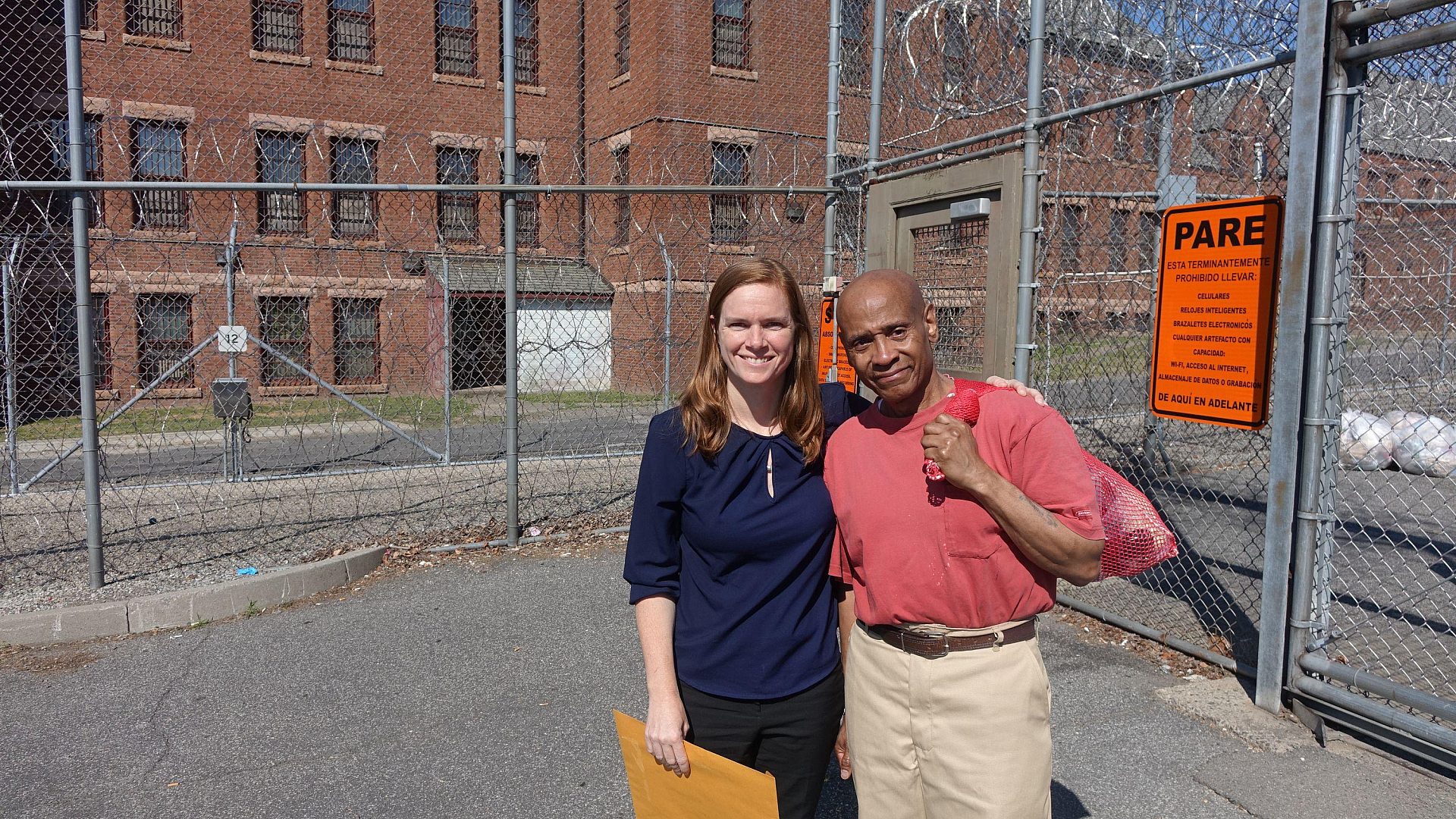

On a clear summer day in July, William Morton left Fishkill Correctional Facility after twenty two years of incarceration. As he passed through the final chain link fence into the parking lot, he was met with a smile, tears, and a hug by Laura Roan, director of Elderly Reentry Initiative (ERI), an Osborne program based in Newburgh, New York.

William Morton is a gentle, reflective 66 year old man who lived in upstate correctional facilities since 1996. Born and raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, William suffered physical and emotional abuse and was homeless by thirteen years of age. Known as “Morton” in prison, when asked how he wanted to be addressed, he said “hmm, call me William, no one’s called me that for twenty years.” Until today, William was one of the almost 250,000 people over 50 that are incarcerated in US state prisons - the fastest-growing segment of the prison population.

Scary, but Exhilarating

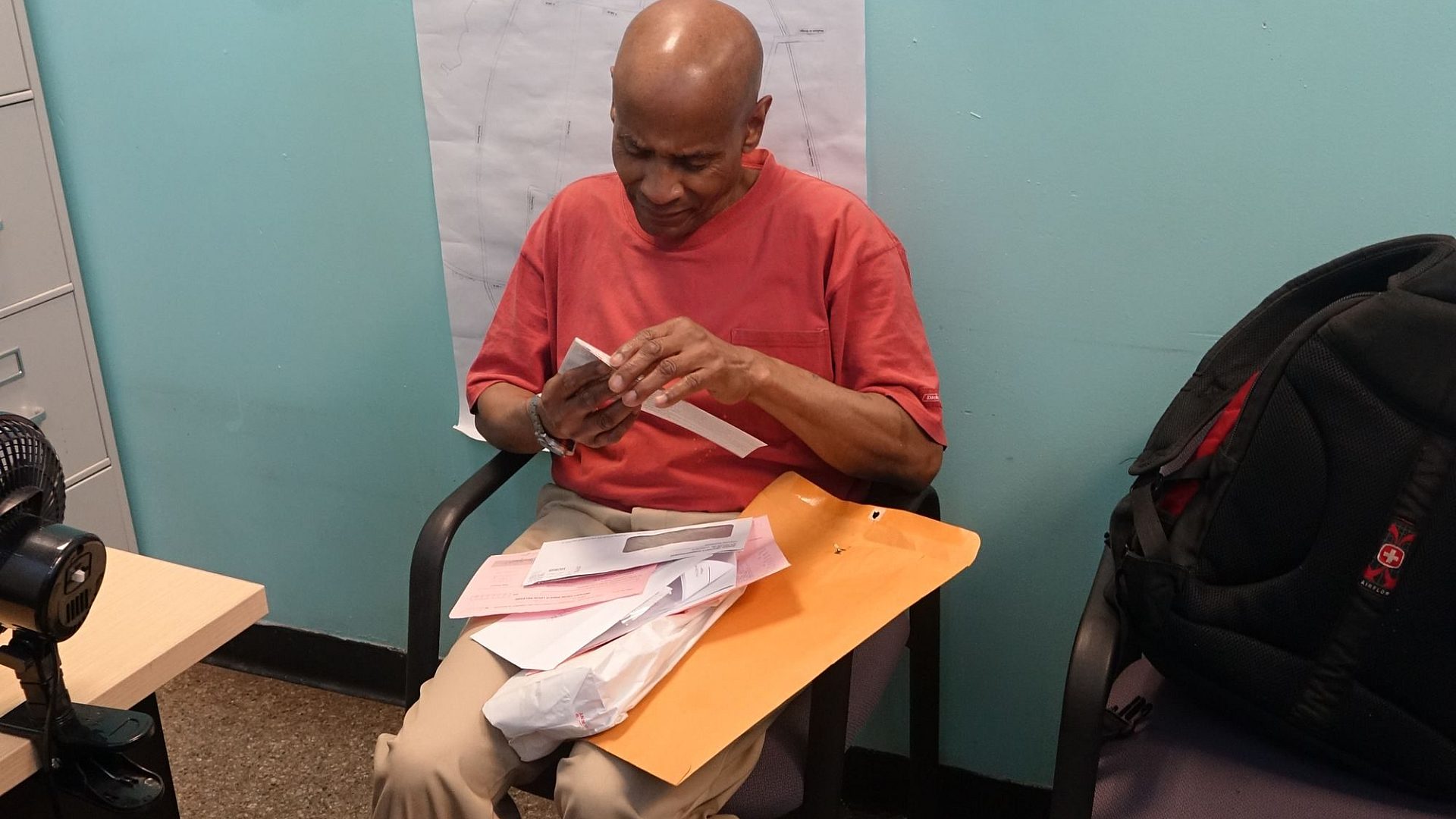

Before leaving the Fishkill parking lot, William and Laura spent ten minutes reviewing his folder of paperwork, which included items like prescriptions, medical reports, and identifying records. While he appears younger than his age, this process was a reminder that William is no longer the middle aged man he was when his sentence began. He walks with a slight limp from a hip replacement he received a few years ago. He is in good health and looks younger than his years. He has large, emotional eyes, and says that people tell him he has a baby face.

As the car pulled away from the facility, William was understandably overwhelmed. When asked how he was feeling, William said “I’m not going to lie… I’m scared, and I’m exhilarated.” In an emotional voice, he considered the challenges living a free life promised - but was resolutely committed to taking them on. He admitted that for many years, he had not wanted or cared to leave prison, because he didn’t think he deserved freedom. As the car parked near the bank where he would cash his work check, he reminded himself of how much he has changed in the previous years, and that he was “a good person” committed to giving back.

William is deeply appreciative toward Laura and the relationship they’ve developed over the last two years. Laura and William met 26 months ago. Initially, he had avoided her in the facility because he didn’t feel he deserved to be released, and so was somewhat ashamed to face her. But, he said “Laura helped (him) to connect the dots” and learn ways to respond to conflict and trauma without violence. Clearly, they are close and comfortable with one another.

Laura has been with ERI since its inception. In 2015, in collaboration with the NYC Department for the Aging and colleagues in academia, corrections, gerontology, reentry and the community, Osborne launched the Elder Reentry Initiative. ERI works with incarcerated older adults as they prepare to return home, connecting them to resources that meet their unique and often unmet needs. Then, upon release, Osborne’s care managers ensure that returning citizens are well cared for in the community.

Strong Connections

After a pastrami sandwich and fries at a Newburgh diner - the first meal William had ordered himself in years - Laura drove William to the Bronx Osborne office to meet his care manager. During the first months of his reentry, an Osborne staff person will help William through initial steps like accompanying William to see his parole officer within the required 24 hour period.

In addition to the support Osborne offers, one of the things William has in his corner is the strong personal connections he has built, both inside and outside. At Fishkill, his seven years of compassionate work as in the Regional Medical Unit (RMU) won him many friends among fellow prisoners, staff, and correctional officers. In addition to housekeeping, he did a lot of “comfort” work - cleaning the infirm, spending time talking to and making hospice patients comfortable. When compiling the portfolio needed during his parole hearing, he collected nine letters of support from prison staff and correctional officers - a very high number of letters, and a reflection of the deep impact he made on people. He spoke fondly of his supervisor, his colleagues, and the patients he worked with at the RMU.

He will clearly miss his job.

He can also rely on friends and loved ones in the community. At an event at Fishkill, William met Gilda, his fiance. Gilda’s letters, calls, and visits were the first that William have received during his entire incarceration, and William credits this relationship with inspiring him to do the work buildin ga portfolio that is necessary to make parole. William is excited to see where living outside might take them. They’ve mutually agreed that until William secures employment and housing - stability - they will take it slow. The toughest decision he made at Rite Aid was picking out the perfect card for Gilda. He plans to give it to her during a date they set for that Sunday, when they will meet in Midtown Manhattan to shop at Macy’s.

Salim, a friend from Fishkill who has been home since April, met William as he arrived at the Bronx office. In prison, they were known as “the Twins”, due to their close relationship and similar physical appearance (they are about the same height and sport bald heads.) While their personalities contrast - Salim is effusive, joking, energetic, while WIlliam is more reserved and quiet- the genuineness of their friendship is clear to any observer. Salim was visibly excited to see William and offered much advice as William went through his paperwork with his care manager.

So, William has some advantages, compared to other elders returning to the community after a long period of incarceration. He does not have a history of substance abuse, and was previously gainfully employed. He built a network of support that includes friends, professionals, and experts, that can help him through inevitable rough spots.

That said, the challenges ahead are common among those returning from a period of incarceration, and sustainable solutions are not easily found. For example, his short term housing at HHC/Bellevue Hospital Sober Living Homes.in Manhattan leaves him a long distance from the support he’ll find at the Bronx Osborne office. He has not had contact with his adoptive parents for decades, nor does he have any siblings or children that could help ease his transition. At the time of writing, he wasn’t sure where he would be working, and he was concerned about the byzantine process of securing benefits and identification. He was not provided with a correct birth certificate when he exited Fishkill, a serious problem for someone reestablishing their identity and access to needed programs and benefits.

Catching Up

One of the many challenges older adults face returning to society is the advancement of technology during their incarceration. However, William was eager to try his new mobile phone, even if it took a few attempts. He ascribes some of his willingness to engage with new technology to keeping up with news, politics, and even fashion while in prison. He is also a voracious reader of fantasy and science fiction. Williams says “reading kept me sane.” He pushed through his unfamiliarity with the smartphone and was texting Gilda by the time Laura pulled on to the southbound Taconic Parkway.

While picking up basic items like deodorant, shaving cream, and a razor at Rite Aid, William noticed a case of fresh eggs and milk. Prisons don’t stock these seemingly common items, so he was excited to see them. He made his choices of toiletries based on recommendations of brands from other prisoners. Laura picked out a pay-as-you-go mobile phone for William, explaining the process of adding minutes and data. William joked that he had no idea what she was talking about, but “I’m sure I’ll learn soon enough.”

Getting Real

By the late afternoon, the intensity of the day was clearly weighing on William. Laura dropped William off at the Bronx office, said her goodbyes, and introduced him to his care manager. Along with his friend Salim, who met William at the front door of the building, William and his care manager worked out a schedule for the next few days. He was chagrined to hear about rules like curfew that would interrupt time he had planned to spend with Gilda. In the first few days, he needed to see his parole officer, visit the HRA office, and get identification at the Department of Motor Vehicles - and all without an accurate birth certificate. William began to experience part of what coming home would mean: a lot of waiting in lines, errands, and hard work ahead.

On the 45 minute train ride from the Bronx to the East Side of Manhattan, Salim and William talked quietly and resolutely with each other about the rules “outside.” While walking the long avenues from the station to Bellevue, William was in turn excited, nervous, exhausted and energized. This would be his first night not sleeping in a prison cell for twenty two years.

During his pastrami sandwich lunch, William talked about what was next for him “I don’t have all that much time left, but I do have some,” he said, “so I want to be positive, stay out of bad situations, and I want to make a difference in people’s lives.” Laura reminded him he already had positively affected many people’s lives, and he said “yeah, I know, I guess I like to.”